44. Sustainable Plans for a Calvo Model#

44.1. Overview#

This is a sequel to this quantecon lecture Time Inconsistency of Ramsey Plans.

That lecture studied a linear-quadratic version of a model that Guillermo Calvo [Calvo, 1978] used to study the time inconsistency of the optimal government plan that emerges when a Stackelberg government (a.k.a. a Ramsey planner) at time

A consequence of that choice is a (rational expectations equilibrium) sequence

[Calvo, 1978] showed that a Ramsey plan would

not emerge from alternative timing protocols and associated supplementary assumptions about what government authorities who set

In this lecture, we explore another set of assumptions about what government authorities who set

We shall assume that there is sequence of separate policymakers; a time

This timing protocol and belief structure leads to a model of a credible government policy, also known as a sustainable plan.

In quantecon lecture Time Inconsistency of Ramsey Plans we used ideas from papers by Cagan [Cagan, 1956], Calvo [Calvo, 1978], and Chang [Chang, 1998].

In addition to those ideas, we’ll also use ideas from Abreu [Abreu, 1988], Stokey [Stokey, 1989], [Stokey, 1991], and Chari and Kehoe [Chari and Kehoe, 1990] to study outcomes under our timing protocol.

44.2. Model Components#

We’ll start with a brief review of the setup.

There is no uncertainty.

Let

The demand for real balances is governed by a perfect foresight version of a Cagan [Cagan, 1956] demand function for real balances:

for

Equation (44.1) asserts that the demand for real balances is inversely related to the public’s expected rate of inflation, which equals the actual rate of inflation because there is no uncertainty here.

(When there is no uncertainty, an assumption of rational expectations that becomes equivalent to perfect foresight).

Subtracting the demand function (44.1) at time

or

Because

Definition: For scalar

We say that a sequence that belongs to

When we assume that the sequence

Insight: In the spirit of Chang [Chang, 1998], equations (44.1) and (44.3) show that

An equivalence class of continuation money growth sequences

That future rates of money creation influence earlier rates of inflation makes timing protocols matter for modeling optimal government policies.

Quantecon lecture Time Inconsistency of Ramsey Plans used this insight to simplify analysis of alternative government policy problems.

44.3. Another Timing Protocol#

The Quantecon lecture Time Inconsistency of Ramsey Plans considered three models of government policy making that differ in

what a policymaker chooses, either a sequence

when a policymaker chooses, either once and for all at time

what a policymaker assumes about how its choice of

In this lecture, there is a sequence of policymakers, each of whom

sets

To set the stage, recall that in a Markov perfect equilibrium

a time

In particular, in a Markov perfect equilibrium, there is a sequence indexed by

By way of contrast, in this lecture there is sequence of distinct policymakers; a time

This timing protocol and belief structure leads to a model of a credible government policy also known as a sustainable plan

The relationship between outcomes under a (Ramsey) timing protocol and the timing protocol and belief structure in this lecture is the subject of a literature on sustainable or credible public policies created by Abreu [Abreu, 1988], [Chari and Kehoe, 1990] [Stokey, 1989], and Stokey [Stokey, 1991].

They discovered conditions under which a Ramsey plan can be rescued from the complaint that it is not credible.

They accomplished this by expanding the description of a plan to include expectations about adverse consequences of deviating from it that can serve to deter deviations.

In this version of our model

the government does not set

instead it sets

the representative agent’s forecasts of

the government at each time

at each

44.3.1. Government Decisions#

The time

We assume the following within-period and between-period timing protocol

for each

at time

The forecasts

Given those expectations and an associated

If the government at

If the government at

44.3.2. Temptation to Deviate from Plan#

The government’s one-period return function

This inequality implies that whenever the policy calls for the

government to set

Disappointing private sector expectations in that way would increase the

government’s current payoff but would have adverse consequences for

subsequent government payoffs because the private sector would alter

its expectations about future settings of

The temporary gain constitutes the government’s temptation to deviate from a plan.

If the government at

44.4. Sustainable or Credible Plan#

We call a plan

The government will choose to confirm prior expectations only if the

long-term loss from disappointing private sector expectations –

coming from the government’s understanding of the way the private sector

adjusts its expectations in response to having its prior

expectations at

The theory of sustainable or credible plans assumes throughout that private sector

expectations about what future governments will do are based on the

assumption that governments at times

This aspect of the theory means that credible plans always come in pairs:

a credible (continuation) plan to be followed if the government at

a credible plan to be followed if the government at

That credible plans come in pairs threaten to bring an explosion of plans to keep track of

each credible plan itself consists of two credible plans

therefore, the number of plans underlying one plan is unbounded

But Dilip Abreu showed how to render manageable the number of plans that must be kept track of.

The key is an object called a self-enforcing plan.

We’ll proceed to compute one.

In addition to what’s in Anaconda, this lecture will use the following libraries:

!pip install --upgrade quantecon

We’ll start with some imports:

import numpy as np

from quantecon import LQ

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import pandas as pd

44.4.1. Abreu’s Self-Enforcing Plan#

A plan

the consequence of disappointing the representative agent’s expectations at time

the consequence of restarting the plan is sufficiently adverse that it forever deters all deviations from the plan

More precisely, a government plan

(Here it is useful to recall that setting

The first line tells the consequences of confirming the representative agent’s expectations by following the plan, while the second line tells the consequences of disappointing the representative agent’s expectations by deviating from the plan.

A consequence of the inequality stated in the definition is that a self-enforcing plan is credible.

Self-enforcing plans can be used to construct other credible plans, including ones with better values.

Thus, where

For this condition to be satisfied it is necessary and sufficient that

The left side of the above inequality is the government’s gain from deviating from the plan, while the right side is the government’s loss from deviating from the plan.

A government never wants to deviate from a credible plan.

Abreu taught us that key step in constructing a credible plan is first constructing a

self-enforcing plan that has a low time

The idea is to use the self-enforcing plan as a continuation plan whenever

the government’s choice at time

We shall use a construction featured in Abreu ([Abreu, 1988]) to construct a

self-enforcing plan with low time

44.4.2. Abreu’s Carrot-Stick Plan#

[Abreu, 1988] invented a way to create a self-enforcing plan with a low initial value.

Imitating his idea, we can construct a self-enforcing plan

Low one-period utilities early are a stick

High one-period utilities later are a carrot

Consider a candidate plan

Denote this sequence by

The sequence of inflation rates implied by this plan,

The value of

For an appropriate

From quantecon lecture Time Inconsistency of Ramsey Plans, we’ll again bring in the Python class ChangLQ that constructs equilibria under timing protocols studied in that lecture.

class ChangLQ:

"""

Class to solve LQ Chang model

"""

def __init__(self, β, c, α=1, u0=1, u1=0.5, u2=3, T=1000, θ_n=200):

# Record parameters

self.α, self.u0, self.u1, self.u2 = α, u0, u1, u2

self.β, self.c, self.T, self.θ_n = β, c, T, θ_n

self.setup_LQ_matrices()

self.solve_LQ_problem()

self.compute_policy_functions()

self.simulate_ramsey_plan()

self.compute_θ_range()

self.compute_value_and_policy()

def setup_LQ_matrices(self):

# LQ Matrices

self.R = -np.array([[self.u0, -self.u1 * self.α / 2],

[-self.u1 * self.α / 2,

-self.u2 * self.α**2 / 2]])

self.Q = -np.array([[-self.c / 2]])

self.A = np.array([[1, 0], [0, (1 + self.α) / self.α]])

self.B = np.array([[0], [-1 / self.α]])

def solve_LQ_problem(self):

# Solve LQ Problem (Subproblem 1)

lq = LQ(self.Q, self.R, self.A, self.B, beta=self.β)

self.P, self.F, self.d = lq.stationary_values()

# Compute g0, g1, and g2 (41.16)

self.g0, self.g1, self.g2 = [-self.P[0, 0],

-2 * self.P[1, 0], -self.P[1, 1]]

# Compute b0 and b1 (41.17)

[[self.b0, self.b1]] = self.F

# Compute d0 and d1 (41.18)

self.cl_mat = (self.A - self.B @ self.F) # Closed loop matrix

[[self.d0, self.d1]] = self.cl_mat[1:]

# Solve Subproblem 2

self.θ_R = -self.P[0, 1] / self.P[1, 1]

# Find the bliss level of θ

self.θ_B = -self.u1 / (self.u2 * self.α)

def compute_policy_functions(self):

# Solve the Markov Perfect Equilibrium

self.μ_MPE = -self.u1 / ((1 + self.α) / self.α * self.c

+ self.α / (1 + self.α)

* self.u2 + self.α**2

/ (1 + self.α) * self.u2)

self.θ_MPE = self.μ_MPE

self.μ_CR = -self.α * self.u1 / (self.u2 * self.α**2 + self.c)

self.θ_CR = self.μ_CR

# Calculate value under MPE and CR economy

self.J_θ = lambda θ_array: - np.array([1, θ_array]) \

@ self.P @ np.array([1, θ_array]).T

self.V_θ = lambda θ: (self.u0 + self.u1 * (-self.α * θ)

- self.u2 / 2 * (-self.α * θ)**2

- self.c / 2 * θ**2) / (1 - self.β)

self.J_MPE = self.V_θ(self.μ_MPE)

self.J_CR = self.V_θ(self.μ_CR)

def simulate_ramsey_plan(self):

# Simulate Ramsey plan for large number of periods

θ_series = np.vstack((np.ones((1, self.T)), np.zeros((1, self.T))))

μ_series = np.zeros(self.T)

J_series = np.zeros(self.T)

θ_series[1, 0] = self.θ_R

[μ_series[0]] = -self.F.dot(θ_series[:, 0])

J_series[0] = self.J_θ(θ_series[1, 0])

for i in range(1, self.T):

θ_series[:, i] = self.cl_mat @ θ_series[:, i-1]

[μ_series[i]] = -self.F @ θ_series[:, i]

J_series[i] = self.J_θ(θ_series[1, i])

self.J_series = J_series

self.μ_series = μ_series

self.θ_series = θ_series

def compute_θ_range(self):

# Find the range of θ in Ramsey plan

θ_LB = min(min(self.θ_series[1, :]), self.θ_B)

θ_UB = max(max(self.θ_series[1, :]), self.θ_MPE)

θ_range = θ_UB - θ_LB

self.θ_LB = θ_LB - 0.05 * θ_range

self.θ_UB = θ_UB + 0.05 * θ_range

self.θ_range = θ_range

def compute_value_and_policy(self):

# Create the θ_space

self.θ_space = np.linspace(self.θ_LB, self.θ_UB, 200)

# Find value function and policy functions over range of θ

self.J_space = np.array([self.J_θ(θ) for θ in self.θ_space])

self.μ_space = -self.F @ np.vstack((np.ones(200), self.θ_space))

x_prime = self.cl_mat @ np.vstack((np.ones(200), self.θ_space))

self.θ_prime = x_prime[1, :]

self.CR_space = np.array([self.V_θ(θ) for θ in self.θ_space])

self.μ_space = self.μ_space[0, :]

# Calculate J_range, J_LB, and J_UB

self.J_range = np.ptp(self.J_space)

self.J_LB = np.min(self.J_space) - 0.05 * self.J_range

self.J_UB = np.max(self.J_space) + 0.05 * self.J_range

Let’s create an instance of ChangLQ with the following parameters:

clq = ChangLQ(β=0.85, c=2)

44.4.3. Example of Self-Enforcing Plan#

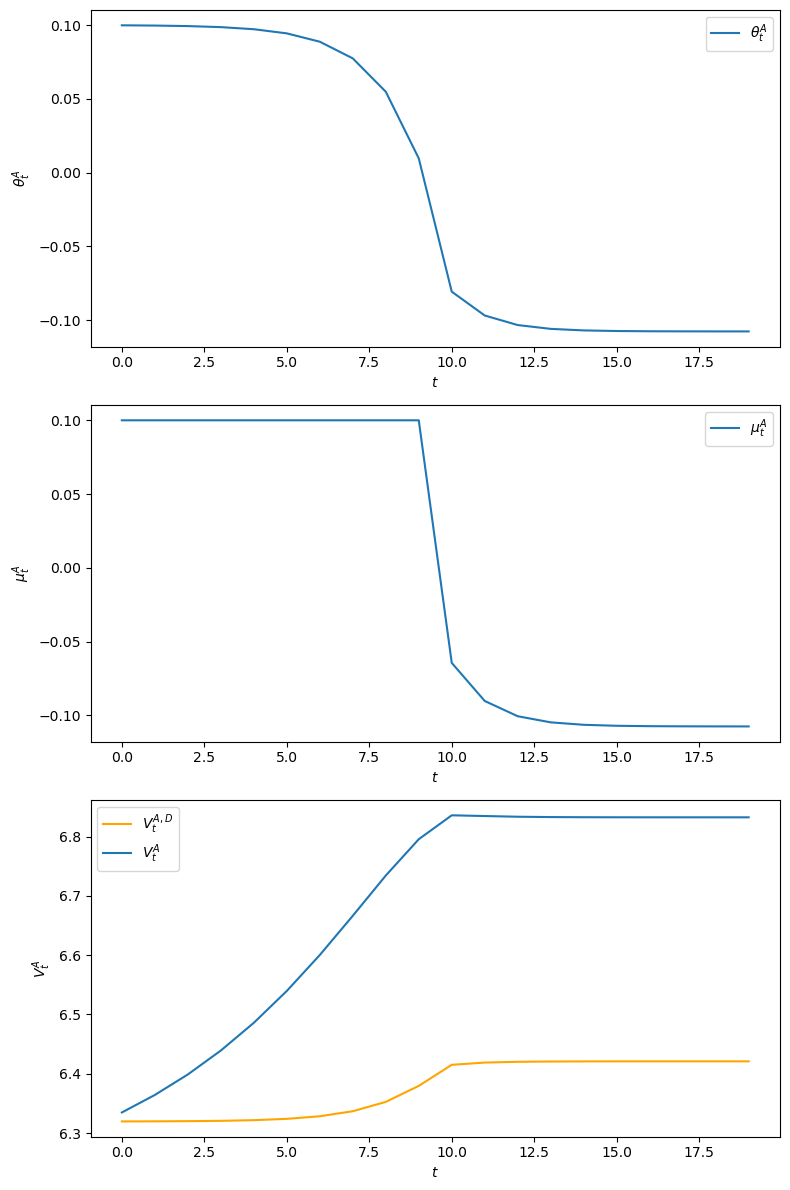

The following example implements an Abreu stick-and-carrot plan.

The government sets

We have computed outcomes for this plan.

For this plan, we plot the

Notice that because the government sets money supply growth high for 10 periods, inflation starts high.

Inflation gradually slowly declines because people expect the government to lower the money growth rate after period

From the 10th period onwards, the inflation rate

To confirm that the plan

In the above graph

We can also verify the inequalities required for

np.all(clq.V_A[0:20] > clq.V_dev[0:20])

True

Given that plan

def check_ramsey(clq, T=1000):

# Make sure Ramsey plan is sustainable

R_dev = np.zeros(T)

for t in range(T):

R_dev[t] = (clq.u0 + clq.u1 * (-clq.θ_series[1, t])

- clq.u2 / 2 * (-clq.θ_series[1, t])**2) \

+ clq.β * clq.V_A[0]

return np.all(clq.J_series > R_dev)

check_ramsey(clq)

True

44.4.4. Recursive Representation of a Sustainable Plan#

We can represent a sustainable plan recursively by taking the

continuation value

We form the following 3-tuple of functions:

In addition to these equations, we need an initial value

The first equation of (44.6) tells the recommended value of

The second equation of (44.6) tells the inflation rate as a function of

The third equation of (44.6) updates the continuation value in a way that

depends on whether the government at

44.5. Whose Plan is It?#

A credible government plan

It is a sequence of actions chosen by the government.

It is a sequence of the representative agent’s forecasts of government actions.

Thus,

Does the government choose policy actions or does it simply confirm prior private sector forecasts of those actions?

An argument in favor of the government chooses interpretation comes from noting that the theory of credible plans builds in a theory that the government each period chooses the action that it wants.

An argument in favor of the simply confirm interpretation is gathered from staring at the key inequality (44.5) that defines a credible policy.

We have also computed credible plans for a government or sequence of governments that choose sequentially.

These include

a self-enforcing plan that gives a low initial value

a better plan – possibly one that attains values associated with Ramsey plan – that is not self-enforcing.