8. Markov Jump Linear Quadratic Dynamic Programming#

In addition to what’s in Anaconda, this lecture will need the following libraries:

!pip install --upgrade quantecon

8.1. Overview#

This lecture describes Markov jump linear quadratic dynamic programming, an extension of the method described in the first LQ control lecture.

Markov jump linear quadratic dynamic programming is described and analyzed in [Do Val et al., 1999] and the references cited there.

The method has been applied to problems in macroeconomics and monetary economics by [Svensson et al., 2008] and [Svensson and Williams, 2009].

The periodic models of seasonality described in chapter 14 of [Hansen and Sargent, 2013] are a special case of Markov jump linear quadratic problems.

Markov jump linear quadratic dynamic programming combines advantages of

the computational simplicity of linear quadratic dynamic programming, with

the ability of finite state Markov chains to represent interesting patterns of random variation.

The idea is to replace the constant matrices that define a linear quadratic dynamic programming problem

with

The state of the Markov chain together with the continuous

For the class of infinite horizon problems being studied in this lecture, we obtain

One of these value functions and one of these decision rules apply in each of the

That is, when the Markov state is in state

8.2. Review of useful LQ dynamic programming formulas#

To begin, it is handy to have the following reminder in mind.

A linear quadratic dynamic programming problem consists of a scalar

discount factor

A triple of matrices

a triple of matrices

The problem is

subject to the transition law for the state.

The optimal decision rule has the form

and the optimal value function is of the form

where

and the constant

and the matrix

With the preceding formulas in mind, we are ready to approach Markov Jump linear quadratic dynamic programming.

8.3. Linked Riccati equations for Markov LQ dynamic programming#

The key idea is to make the matrices

This makes decision rules depend on the Markov state, and so fluctuate through time in limited ways.

In particular, we use the following extension of a discrete-time linear quadratic dynamic programming problem.

We let

Here

We’ll switch between labeling today’s state as

The decision-maker solves the minimization problem:

with

subject to linear laws of motion with matrices

where

The optimal decision rule for this problem has the form

and the optimal value functions are of the form

or equivalently

The optimal value functions

The matrices

and the

8.4. Applications#

We now describe Python code and some examples.

To begin, we import these Python modules

import numpy as np

import quantecon as qe

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from mpl_toolkits.mplot3d import Axes3D

# Set discount factor

β = 0.95

8.5. Example 1#

This example is a version of a classic problem of optimally adjusting a variable

This provides a model of gradual adjustment.

Given

where the one-period payoff function is

We can think of

We assume that

Denote the state transition matrix for Markov state

Let

We can represent the one-period payoff function

and the state-transition law as

def construct_arrays1(f1_vals=[1. ,1.],

f2_vals=[1., 1.],

d_vals=[1., 1.]):

"""

Construct matrices that map the problem described in example 1

into a Markov jump linear quadratic dynamic programming problem

"""

# Number of Markov states

m = len(f1_vals)

# Number of state and control variables

n, k = 2, 1

# Construct sets of matrices for each state

As = [np.eye(n) for i in range(m)]

Bs = [np.array([[1, 0]]).T for i in range(m)]

Rs = np.zeros((m, n, n))

Qs = np.zeros((m, k, k))

for i in range(m):

Rs[i, 0, 0] = f2_vals[i]

Rs[i, 1, 0] = - f1_vals[i] / 2

Rs[i, 0, 1] = - f1_vals[i] / 2

Qs[i, 0, 0] = d_vals[i]

Cs, Ns = None, None

# Compute the optimal k level of the payoff function in each state

k_star = np.empty(m)

for i in range(m):

k_star[i] = f1_vals[i] / (2 * f2_vals[i])

return Qs, Rs, Ns, As, Bs, Cs, k_star

The continuous part of the state

state_vec1 = ["k", "constant term"]

We start with a Markov transition matrix that makes the Markov state be strictly periodic:

We set

In contrast to

We set the adjustment cost to be lower in Markov state

The following code forms a Markov switching LQ problem and computes the optimal value functions and optimal decision rules for each Markov state

# Construct Markov transition matrix

Π1 = np.array([[0., 1.],

[1., 0.]])

# Construct matrices

Qs, Rs, Ns, As, Bs, Cs, k_star = construct_arrays1(d_vals=[1., 0.5])

# Construct a Markov Jump LQ problem

ex1_a = qe.LQMarkov(Π1, Qs, Rs, As, Bs, Cs=Cs, Ns=Ns, beta=β)

# Solve for optimal value functions and decision rules

ex1_a.stationary_values();

Let’s look at the value function matrices and the decision rules for each Markov state

# P(s)

ex1_a.Ps

array([[[ 1.56626026, -0.78313013],

[-0.78313013, -4.60843493]],

[[ 1.37424214, -0.68712107],

[-0.68712107, -4.65643947]]])

# d(s) = 0, since there is no randomness

ex1_a.ds

array([0., 0.])

# F(s)

ex1_a.Fs

array([[[ 0.56626026, -0.28313013]],

[[ 0.74848427, -0.37424214]]])

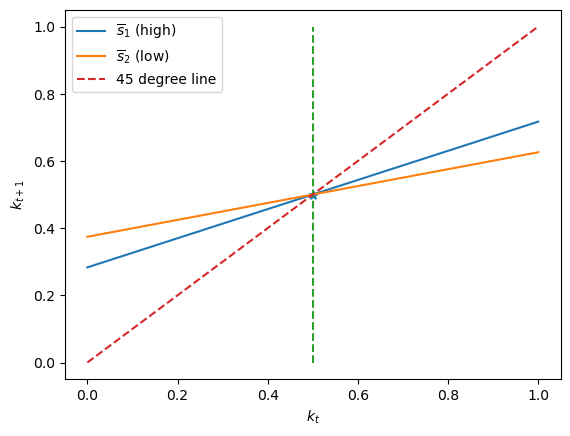

Now we’ll plot the decision rules and see if they make sense

# Plot the optimal decision rules

k_grid = np.linspace(0., 1., 100)

# Optimal choice in state s1

u1_star = - ex1_a.Fs[0, 0, 1] - ex1_a.Fs[0, 0, 0] * k_grid

# Optimal choice in state s2

u2_star = - ex1_a.Fs[1, 0, 1] - ex1_a.Fs[1, 0, 0] * k_grid

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

ax.plot(k_grid, k_grid + u1_star, label=r"$\overline{s}_1$ (high)")

ax.plot(k_grid, k_grid + u2_star, label=r"$\overline{s}_2$ (low)")

# The optimal k*

ax.scatter([0.5, 0.5], [0.5, 0.5], marker="*")

ax.plot([k_star[0], k_star[0]], [0., 1.0], '--')

# 45 degree line

ax.plot([0., 1.], [0., 1.], '--', label="45 degree line")

ax.set_xlabel("$k_t$")

ax.set_ylabel("$k_{t+1}$")

ax.legend()

plt.show()

The above graph plots

It also plots the 45 degree line.

Notice that the two

Evidently, the optimal decision rule in Markov state

This happens because when

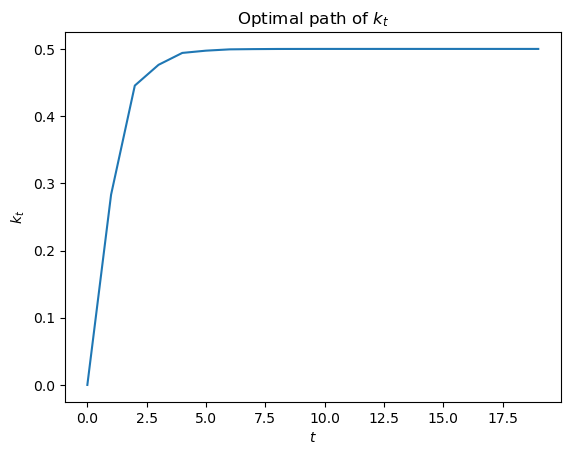

# Compute time series

T = 20

x0 = np.array([[0., 1.]]).T

x_path = ex1_a.compute_sequence(x0, ts_length=T)[0]

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

ax.plot(range(T), x_path[0, :-1])

ax.set_xlabel("$t$")

ax.set_ylabel("$k_t$")

ax.set_title("Optimal path of $k_t$")

plt.show()

Now we’ll depart from the preceding transition matrix that made the Markov state be strictly periodic.

We’ll begin with symmetric transition matrices of the form

λ = 0.8 # high λ

Π2 = np.array([[1-λ, λ],

[λ, 1-λ]])

ex1_b = qe.LQMarkov(Π2, Qs, Rs, As, Bs, Cs=Cs, Ns=Ns, beta=β)

ex1_b.stationary_values();

ex1_b.Fs

array([[[ 0.57291724, -0.28645862]],

[[ 0.74434525, -0.37217263]]])

λ = 0.2 # low λ

Π2 = np.array([[1-λ, λ],

[λ, 1-λ]])

ex1_b = qe.LQMarkov(Π2, Qs, Rs, As, Bs, Cs=Cs, Ns=Ns, beta=β)

ex1_b.stationary_values();

ex1_b.Fs

array([[[ 0.59533259, -0.2976663 ]],

[[ 0.72818728, -0.36409364]]])

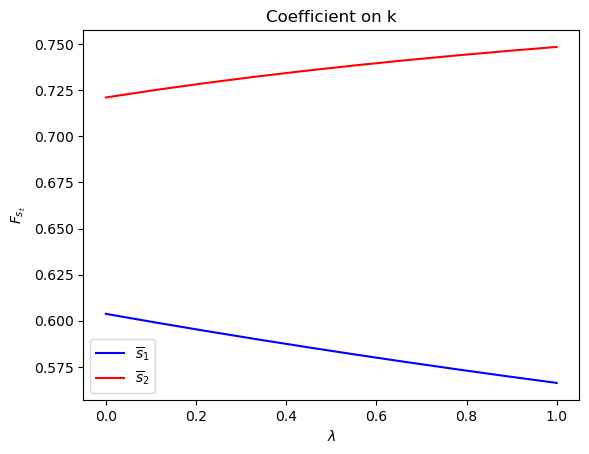

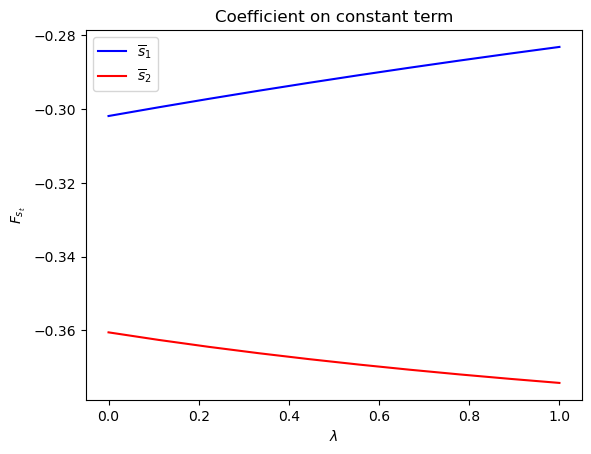

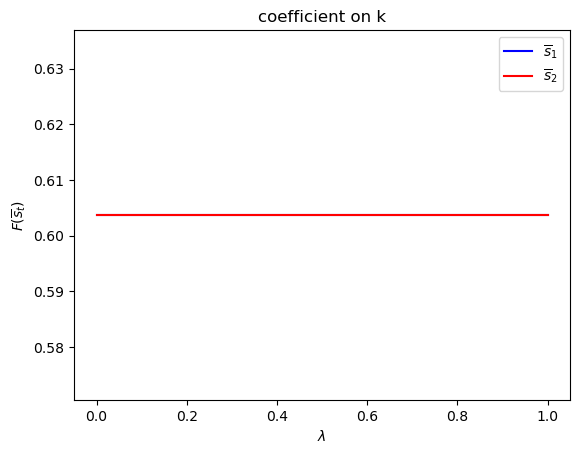

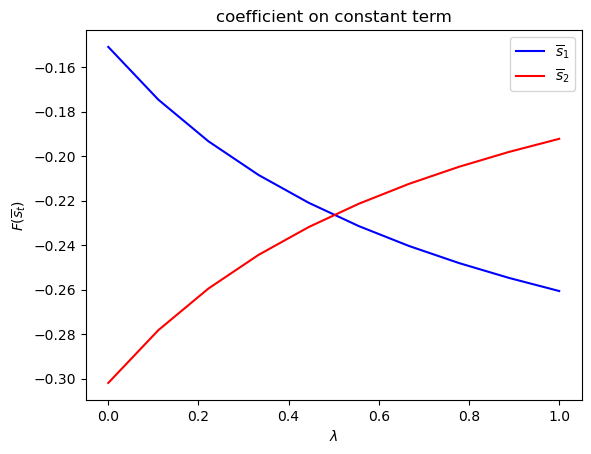

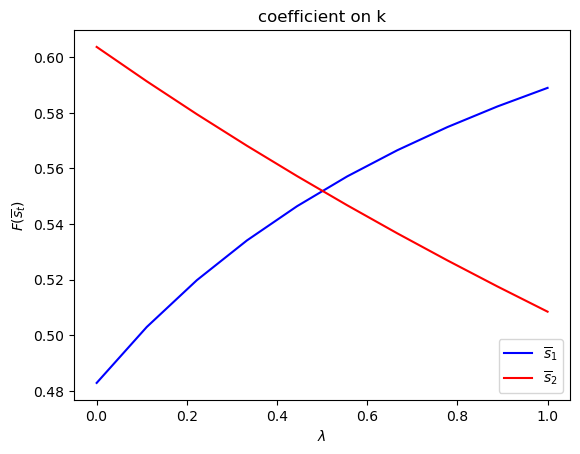

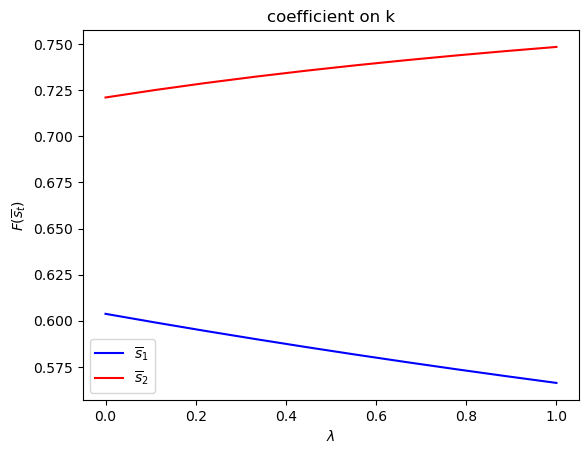

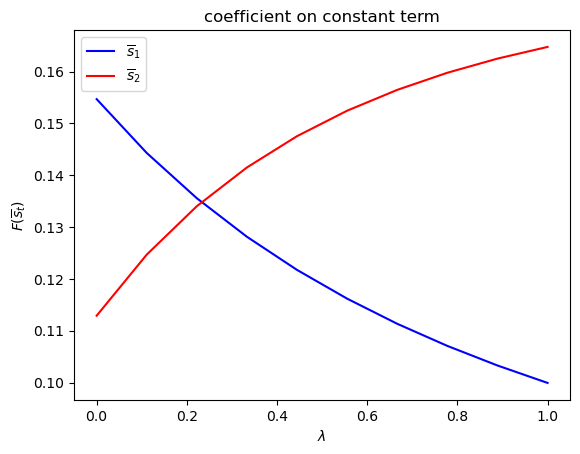

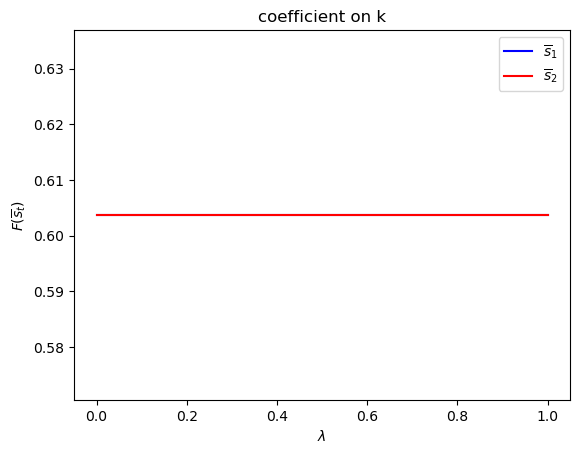

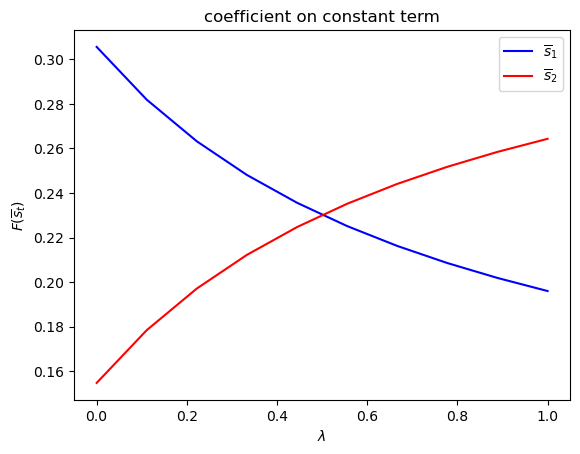

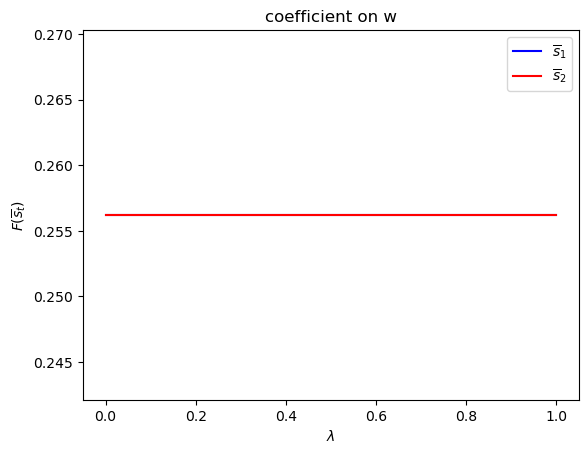

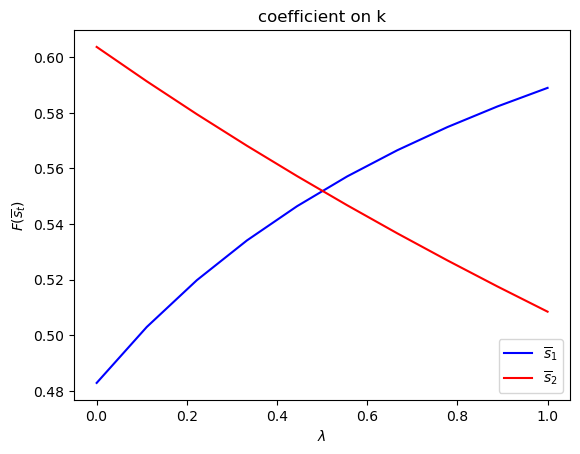

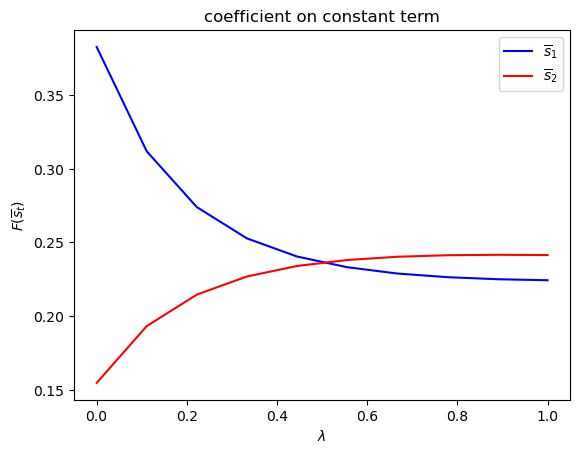

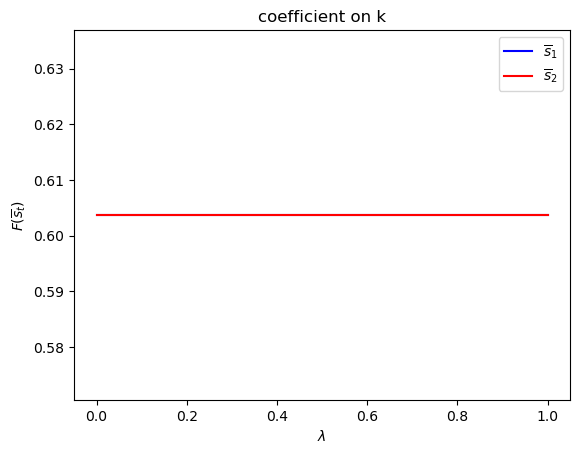

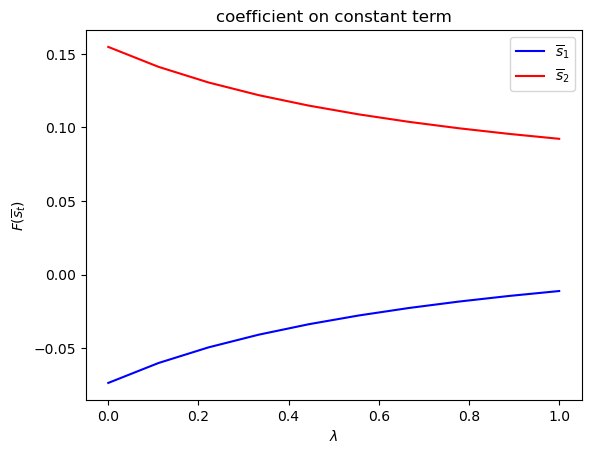

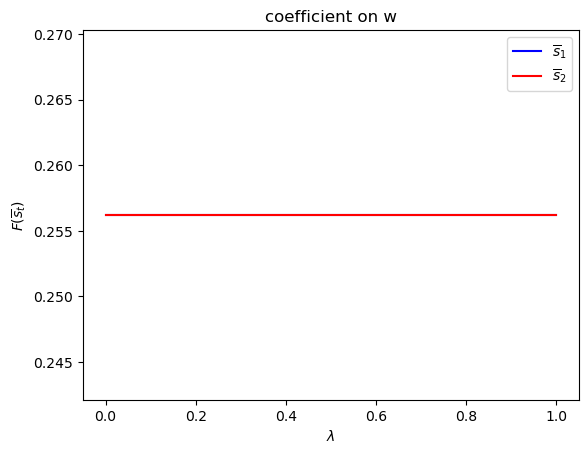

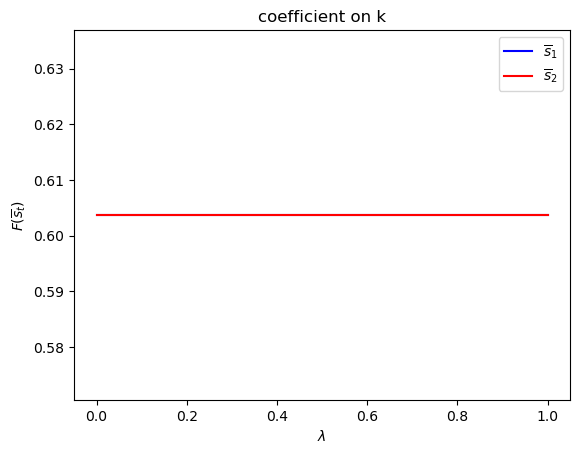

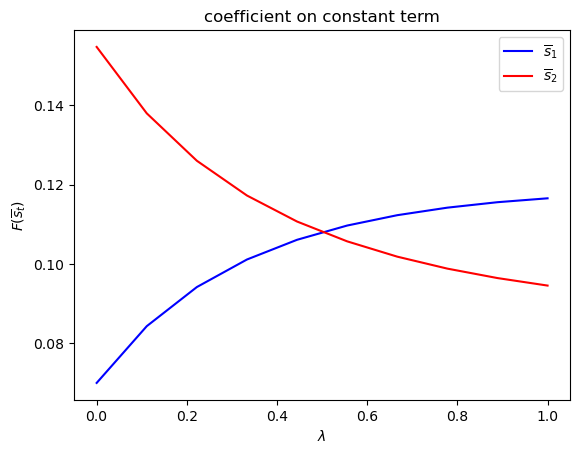

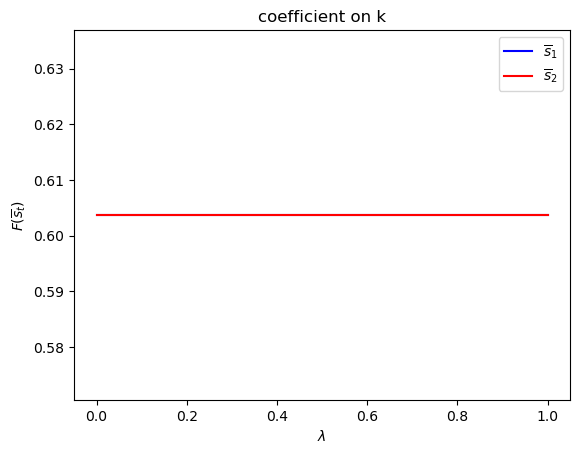

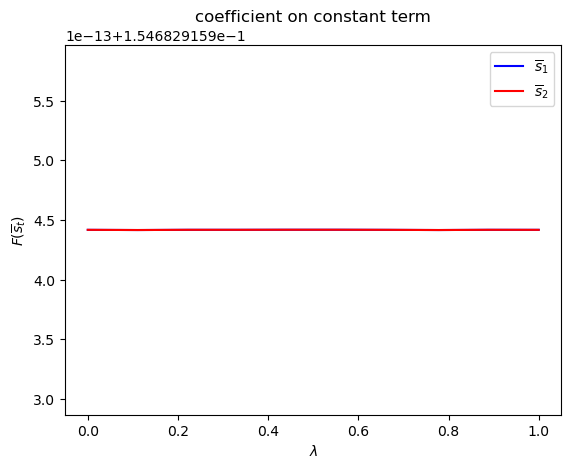

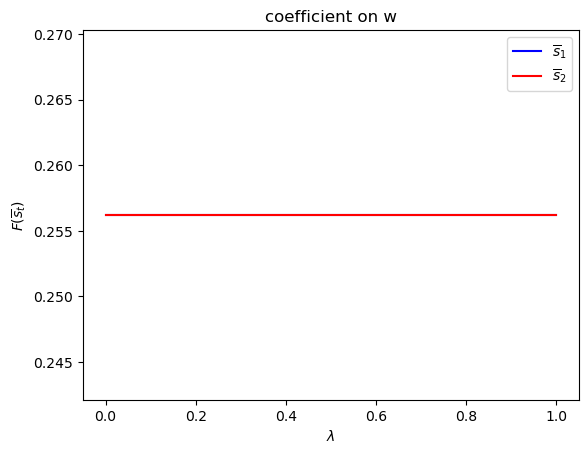

We can plot optimal decision rules associated with different

λ_vals = np.linspace(0., 1., 10)

F1 = np.empty((λ_vals.size, 2))

F2 = np.empty((λ_vals.size, 2))

for i, λ in enumerate(λ_vals):

Π2 = np.array([[1-λ, λ],

[λ, 1-λ]])

ex1_b = qe.LQMarkov(Π2, Qs, Rs, As, Bs, Cs=Cs, Ns=Ns, beta=β)

ex1_b.stationary_values();

F1[i, :] = ex1_b.Fs[0, 0, :]

F2[i, :] = ex1_b.Fs[1, 0, :]

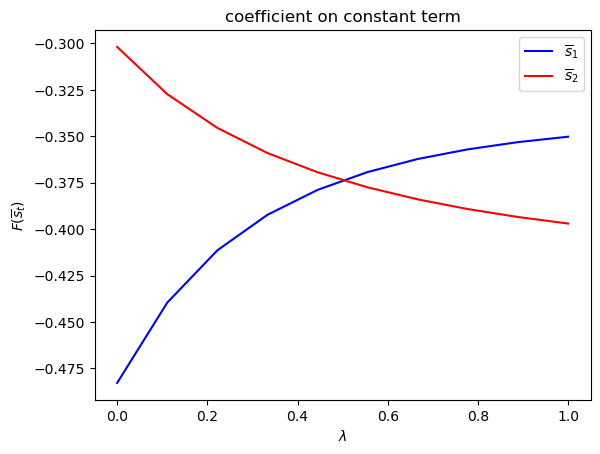

for i, state_var in enumerate(state_vec1):

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

ax.plot(λ_vals, F1[:, i], label=r"$\overline{s}_1$", color="b")

ax.plot(λ_vals, F2[:, i], label=r"$\overline{s}_2$", color="r")

ax.set_xlabel(r"$\lambda$")

ax.set_ylabel("$F_{s_t}$")

ax.set_title(f"Coefficient on {state_var}")

ax.legend()

plt.show()

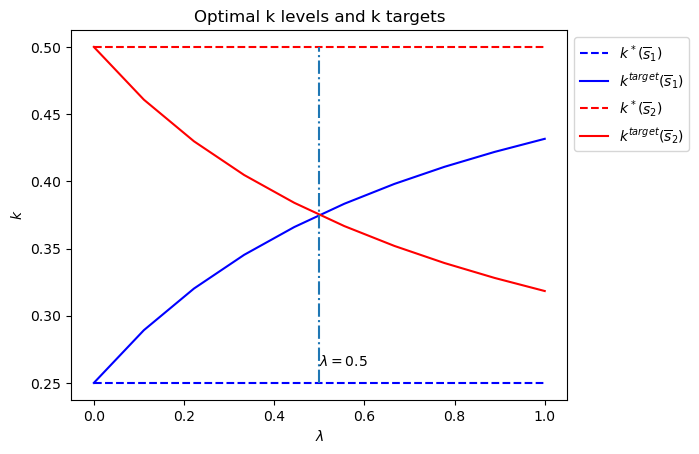

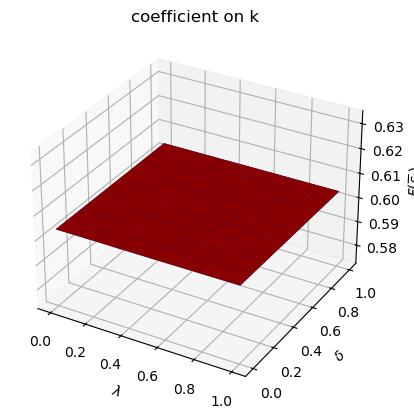

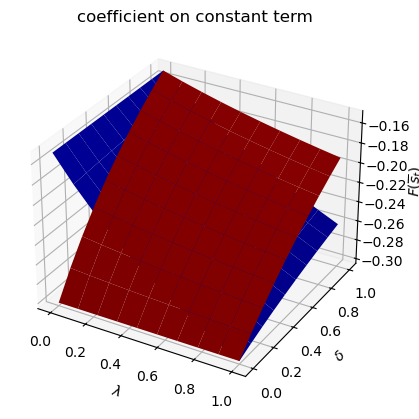

Notice how the decision rules’ constants and slopes behave as functions

of

Evidently, as the Markov chain becomes more nearly periodic (i.e., as

Now let’s study situations in which the Markov transition matrix

λ, δ = 0.8, 0.2

Π3 = np.array([[1-λ, λ],

[δ, 1-δ]])

ex1_b = qe.LQMarkov(Π3, Qs, Rs, As, Bs, Cs=Cs, Ns=Ns, beta=β)

ex1_b.stationary_values();

ex1_b.Fs

array([[[ 0.57169781, -0.2858489 ]],

[[ 0.72749075, -0.36374537]]])

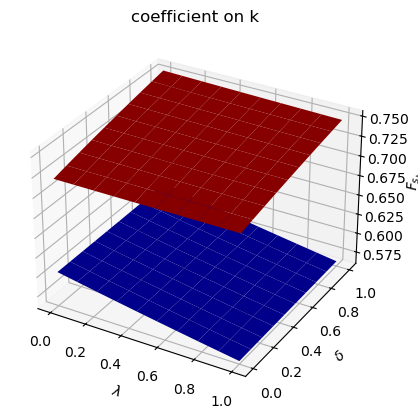

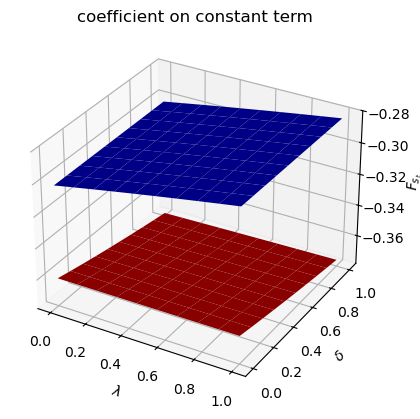

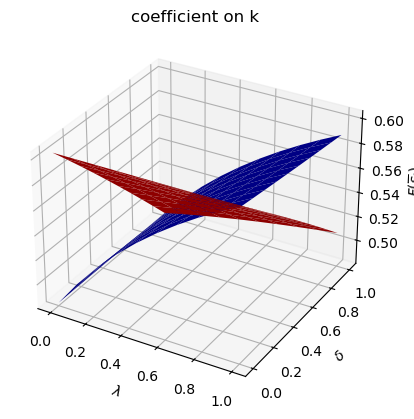

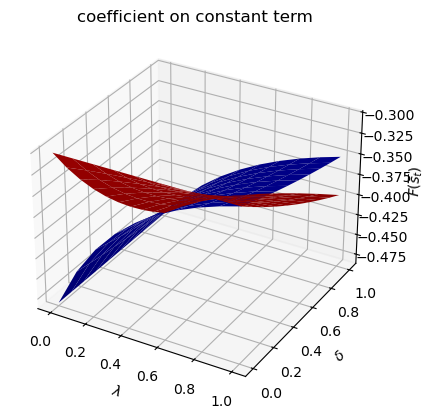

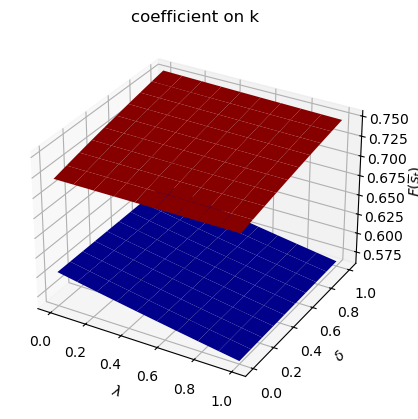

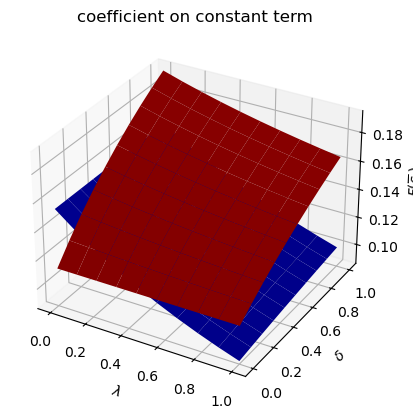

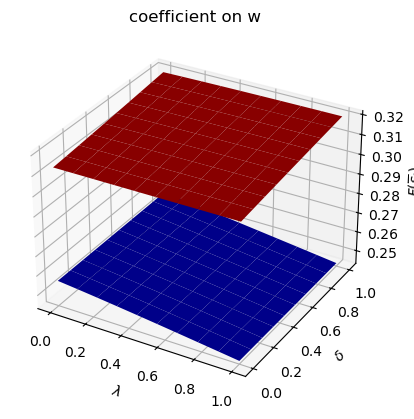

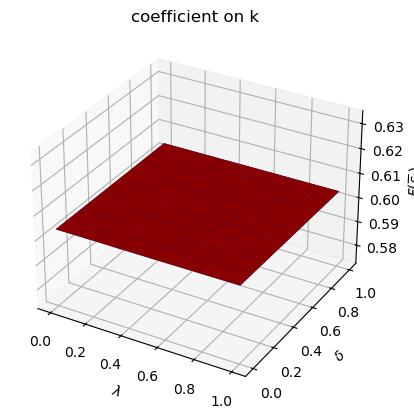

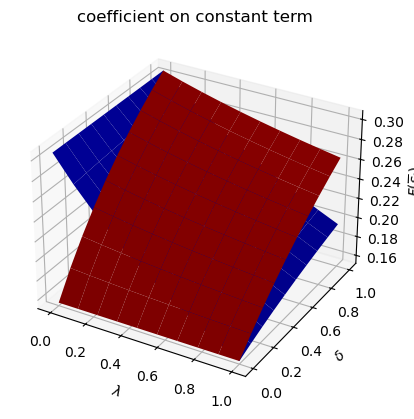

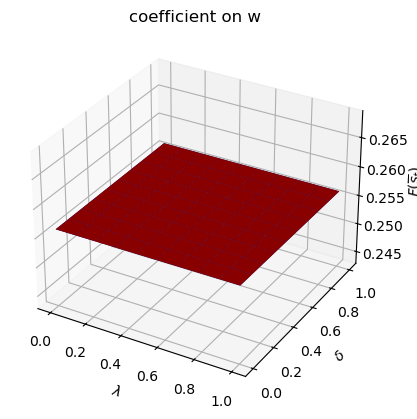

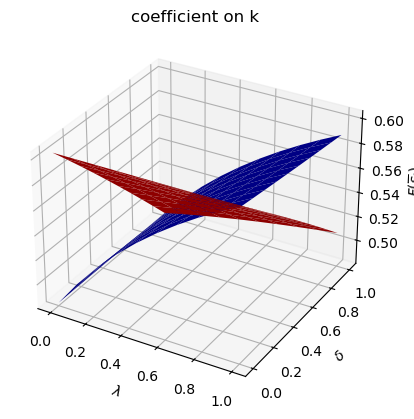

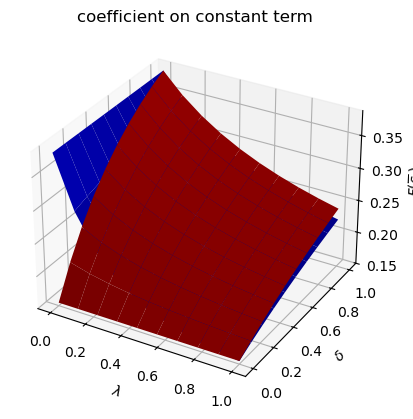

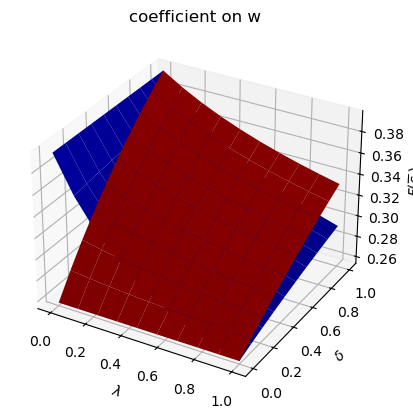

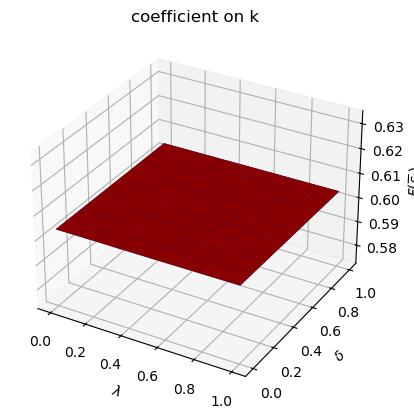

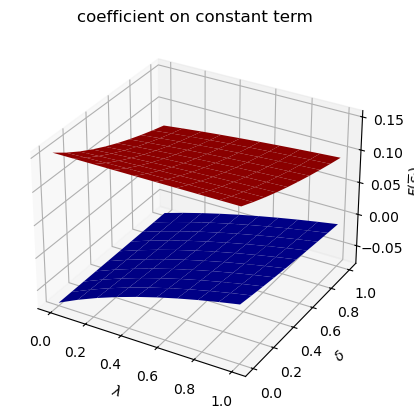

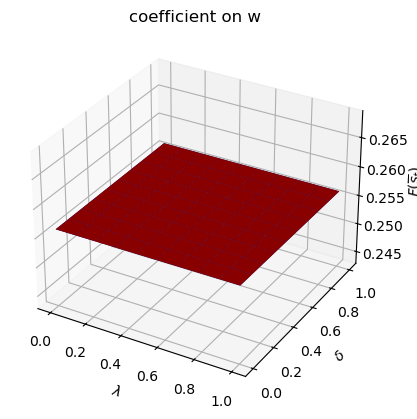

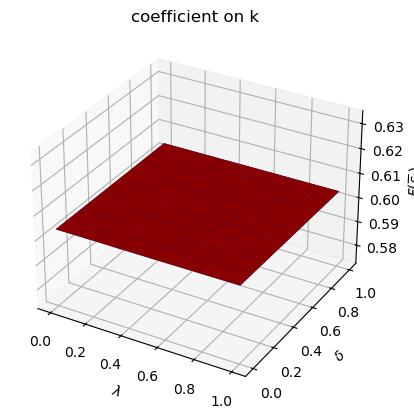

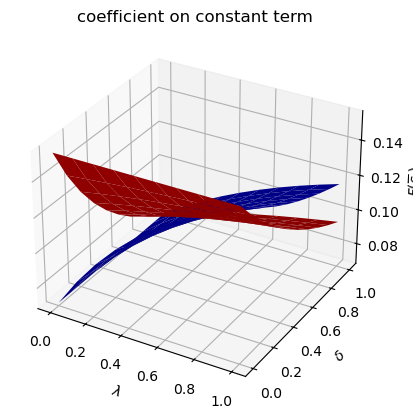

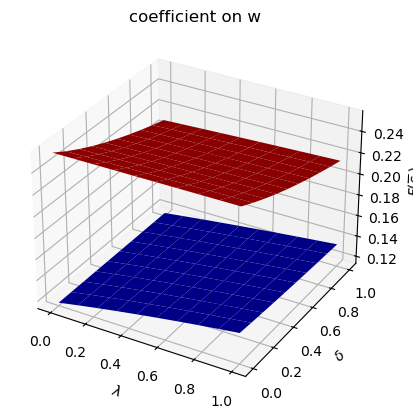

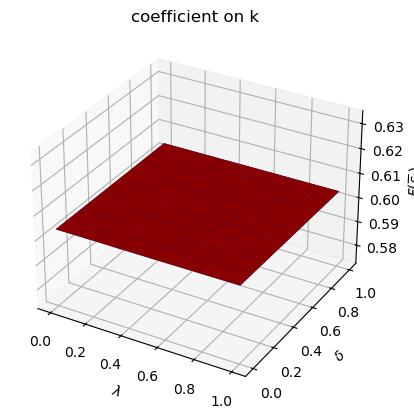

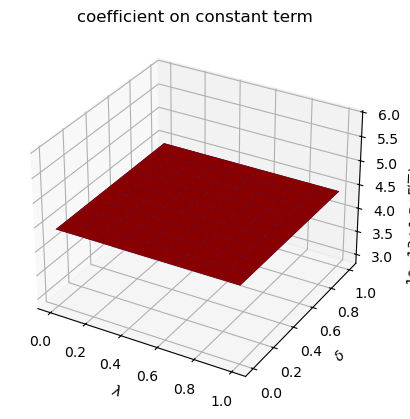

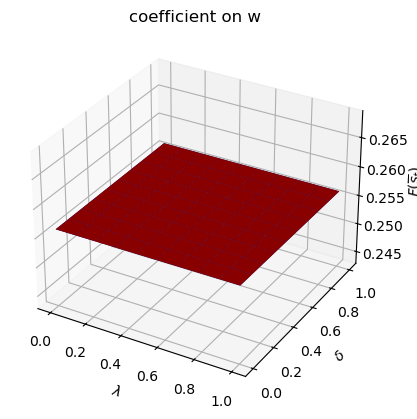

We can plot optimal decision rules for different

λ_vals = np.linspace(0., 1., 10)

δ_vals = np.linspace(0., 1., 10)

λ_grid = np.empty((λ_vals.size, δ_vals.size))

δ_grid = np.empty((λ_vals.size, δ_vals.size))

F1_grid = np.empty((λ_vals.size, δ_vals.size, len(state_vec1)))

F2_grid = np.empty((λ_vals.size, δ_vals.size, len(state_vec1)))

for i, λ in enumerate(λ_vals):

λ_grid[i, :] = λ

δ_grid[i, :] = δ_vals

for j, δ in enumerate(δ_vals):

Π3 = np.array([[1-λ, λ],

[δ, 1-δ]])

ex1_b = qe.LQMarkov(Π3, Qs, Rs, As, Bs, Cs=Cs, Ns=Ns, beta=β)

ex1_b.stationary_values();

F1_grid[i, j, :] = ex1_b.Fs[0, 0, :]

F2_grid[i, j, :] = ex1_b.Fs[1, 0, :]

for i, state_var in enumerate(state_vec1):

fig = plt.figure()

ax = fig.add_subplot(111, projection='3d')

# high adjustment cost, blue surface

ax.plot_surface(λ_grid, δ_grid, F1_grid[:, :, i], color="b")

# low adjustment cost, red surface

ax.plot_surface(λ_grid, δ_grid, F2_grid[:, :, i], color="r")

ax.set_xlabel(r"$\lambda$")

ax.set_ylabel(r"$\delta$")

ax.set_zlabel("$F_{s_t}$")

ax.set_title(f"coefficient on {state_var}")

plt.show()

The following code defines a wrapper function that computes optimal decision rules for cases with different Markov transition matrices

def run(construct_func, vals_dict, state_vec):

"""

A Wrapper function that repeats the computation above

for different cases

"""

Qs, Rs, Ns, As, Bs, Cs, k_star = construct_func(**vals_dict)

# Symmetric Π

# Notice that pure periodic transition is a special case

# when λ=1

print("symmetric Π case:\n")

λ_vals = np.linspace(0., 1., 10)

F1 = np.empty((λ_vals.size, len(state_vec)))

F2 = np.empty((λ_vals.size, len(state_vec)))

for i, λ in enumerate(λ_vals):

Π2 = np.array([[1-λ, λ],

[λ, 1-λ]])

mplq = qe.LQMarkov(Π2, Qs, Rs, As, Bs, Cs=Cs, Ns=Ns, beta=β)

mplq.stationary_values();

F1[i, :] = mplq.Fs[0, 0, :]

F2[i, :] = mplq.Fs[1, 0, :]

for i, state_var in enumerate(state_vec):

fig = plt.figure()

ax = fig.add_subplot(111)

ax.plot(λ_vals, F1[:, i], label=r"$\overline{s}_1$", color="b")

ax.plot(λ_vals, F2[:, i], label=r"$\overline{s}_2$", color="r")

ax.set_xlabel(r"$\lambda$")

ax.set_ylabel(r"$F(\overline{s}_t)$")

ax.set_title(f"coefficient on {state_var}")

ax.legend()

plt.show()

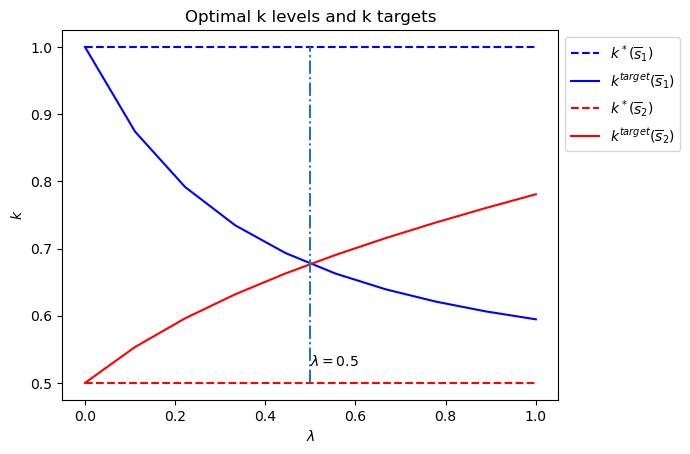

# Plot optimal k*_{s_t} and k that optimal policies are targeting

# only for example 1

if state_vec == ["k", "constant term"]:

fig = plt.figure()

ax = fig.add_subplot(111)

for i in range(2):

F = [F1, F2][i]

c = ["b", "r"][i]

ax.plot([0, 1], [k_star[i], k_star[i]], "--",

color=c, label=r"$k^*(\overline{s}_"+str(i+1)+")$")

ax.plot(λ_vals, - F[:, 1] / F[:, 0], color=c,

label=r"$k^{target}(\overline{s}_"+str(i+1)+")$")

# Plot a vertical line at λ=0.5

ax.plot([0.5, 0.5], [min(k_star), max(k_star)], "-.")

ax.set_xlabel(r"$\lambda$")

ax.set_ylabel("$k$")

ax.set_title("Optimal k levels and k targets")

ax.text(0.5, min(k_star)+(max(k_star)-min(k_star))/20, r"$\lambda=0.5$")

ax.legend(bbox_to_anchor=(1., 1.))

plt.show()

# Asymmetric Π

print("asymmetric Π case:\n")

δ_vals = np.linspace(0., 1., 10)

λ_grid = np.empty((λ_vals.size, δ_vals.size))

δ_grid = np.empty((λ_vals.size, δ_vals.size))

F1_grid = np.empty((λ_vals.size, δ_vals.size, len(state_vec)))

F2_grid = np.empty((λ_vals.size, δ_vals.size, len(state_vec)))

for i, λ in enumerate(λ_vals):

λ_grid[i, :] = λ

δ_grid[i, :] = δ_vals

for j, δ in enumerate(δ_vals):

Π3 = np.array([[1-λ, λ],

[δ, 1-δ]])

mplq = qe.LQMarkov(Π3, Qs, Rs, As, Bs, Cs=Cs, Ns=Ns, beta=β)

mplq.stationary_values();

F1_grid[i, j, :] = mplq.Fs[0, 0, :]

F2_grid[i, j, :] = mplq.Fs[1, 0, :]

for i, state_var in enumerate(state_vec):

fig = plt.figure()

ax = fig.add_subplot(111, projection='3d')

ax.plot_surface(λ_grid, δ_grid, F1_grid[:, :, i], color="b")

ax.plot_surface(λ_grid, δ_grid, F2_grid[:, :, i], color="r")

ax.set_xlabel(r"$\lambda$")

ax.set_ylabel(r"$\delta$")

ax.set_zlabel(r"$F(\overline{s}_t)$")

ax.set_title(f"coefficient on {state_var}")

plt.show()

To illustrate the code with another example, we shall set

Thus, the sole role of the Markov jump state

The example below reveals much about the structure of the optimum problem and optimal policies.

Only

So there are different

We denote a target

We call

When

But when

The switch happens at

Below we plot an additional figure that shows optimal

run(construct_arrays1, {"f1_vals":[0.5, 1.]}, state_vec1)

symmetric Π case:

asymmetric Π case:

Set

run(construct_arrays1, {"f2_vals":[0.5, 1.]}, state_vec1)

symmetric Π case:

asymmetric Π case:

8.6. Example 2#

We now add to the example 1 setup another state variable

We think of

To capture this idea, we add to the decision-maker’s one-period payoff

function the product of

We now let the continuous part of the state at time

We can write the one-period payoff function

and the state-transition law as

def construct_arrays2(f1_vals=[1. ,1.],

f2_vals=[1., 1.],

d_vals=[1., 1.],

α0_vals=[1., 1.],

ρ_vals=[0.9, 0.9],

σ_vals=[1., 1.]):

"""

Construct matrices that maps the problem described in example 2

into a Markov jump linear quadratic dynamic programming problem.

"""

m = len(f1_vals)

n, k, j = 3, 1, 1

Rs = np.zeros((m, n, n))

Qs = np.zeros((m, k, k))

As = np.zeros((m, n, n))

Bs = np.zeros((m, n, k))

Cs = np.zeros((m, n, j))

for i in range(m):

Rs[i, 0, 0] = f2_vals[i]

Rs[i, 1, 0] = - f1_vals[i] / 2

Rs[i, 0, 1] = - f1_vals[i] / 2

Rs[i, 0, 2] = 1/2

Rs[i, 2, 0] = 1/2

Qs[i, 0, 0] = d_vals[i]

As[i, 0, 0] = 1

As[i, 1, 1] = 1

As[i, 2, 1] = α0_vals[i]

As[i, 2, 2] = ρ_vals[i]

Bs[i, :, :] = np.array([[1, 0, 0]]).T

Cs[i, :, :] = np.array([[0, 0, σ_vals[i]]]).T

Ns = None

k_star = None

return Qs, Rs, Ns, As, Bs, Cs, k_star

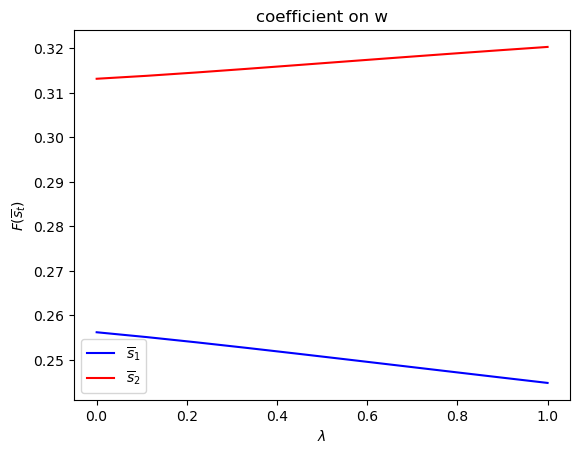

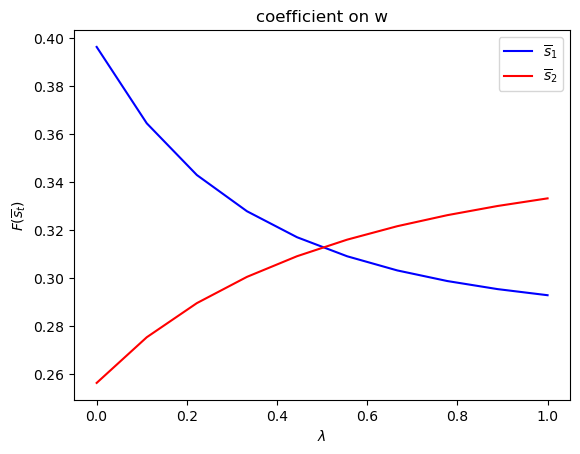

state_vec2 = ["k", "constant term", "w"]

Only

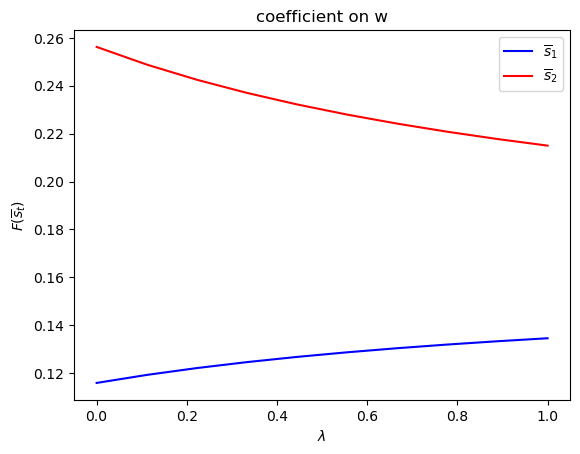

run(construct_arrays2, {"d_vals":[1., 0.5]}, state_vec2)

symmetric Π case:

asymmetric Π case:

Only

run(construct_arrays2, {"f1_vals":[0.5, 1.]}, state_vec2)

symmetric Π case:

asymmetric Π case:

Only

run(construct_arrays2, {"f2_vals":[0.5, 1.]}, state_vec2)

symmetric Π case:

asymmetric Π case:

Only

run(construct_arrays2, {"α0_vals":[0.5, 1.]}, state_vec2)

symmetric Π case:

asymmetric Π case:

Only

run(construct_arrays2, {"ρ_vals":[0.5, 0.9]}, state_vec2)

symmetric Π case:

asymmetric Π case:

Only

run(construct_arrays2, {"σ_vals":[0.5, 1.]}, state_vec2)

symmetric Π case:

asymmetric Π case:

8.7. More examples#

The following lectures describe how Markov jump linear quadratic dynamic programming can be used to extend the [Barro, 1979] model of optimal tax-smoothing and government debt in several interesting directions